While a member of the public may have the best intentions trying to save an animal, they could unknowingly cause more harm than good. Instead of stepping in to try to care for an animal, your best plan of action is to call the experts at Dane County Humane Society’s Wildlife Center. Wildlife rehabilitators are trained and licensed to care for animals in this type of condition.

Staff and volunteers at DCHS’s Wildlife Center regularly advise the public not to provide food or water to injured, sick, or orphaned wild animals because doing so can pose a variety of risks. For example, young animals are constantly growing and eager to eat; however, if fed too quickly, they could develop aspiration pneumonia or refeeding syndrome. Refeeding syndrome is the process of incorrectly reintroducing food after malnourishment or starvation, which can be fatal. Other common concerns include animals suffering from head trauma that fall into a water dish, becoming wet and hypothermic, or people offering food items that are inappropriate for a particular species, such as giving bread to birds. Plus, wild animals often have parasites or other diseases that may be transmitted to other people or companion animals .

The longer a wild animal goes without receiving professional medical care, the more likely it is to have complications that could prevent it from being returned to the wild, according to Wildlife Center staff. In addition, any attempted medical care by the general public can hurt wildlife and potentially worsen their injuries.

“The best thing that can be done for a wild animal is getting it to a licensed rehabilitator as soon as possible,” says Paige Pederson, Wildlife Operations Supervisor.

Some people take injured and even healthy squirrels, turtles, or other native creatures into their homes for an extended period of time, treating them like pets. This is not only illegal, it can also cause long-term and sometimes permanent harm to these animals.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the state’s captive wildlife regulations allow a person to possess a wild animal for up to 24 hours for the purpose of transferring that animal to an appropriately licensed individual, such as a licensed wildlife rehabilitator at the Wildlife Center.

“Wild animals are not domesticated for life with humans, and should live their life in the wild as intended,” Paige says.

In addition, members of the general public aren’t trained to provide proper nutrition or medical care for these animals.

“Wild species have highly specialized needs in terms of diet for proper vitamin and mineral balance, housing, enrichment, temperature, and lighting,” explains Paige. “Too much or too little of any of these aspects of care can be detrimental depending on the species, age, and injury.”

The Wildlife Center is currently treating several wild animals for medical and behavioral concerns after they were kept as pets.

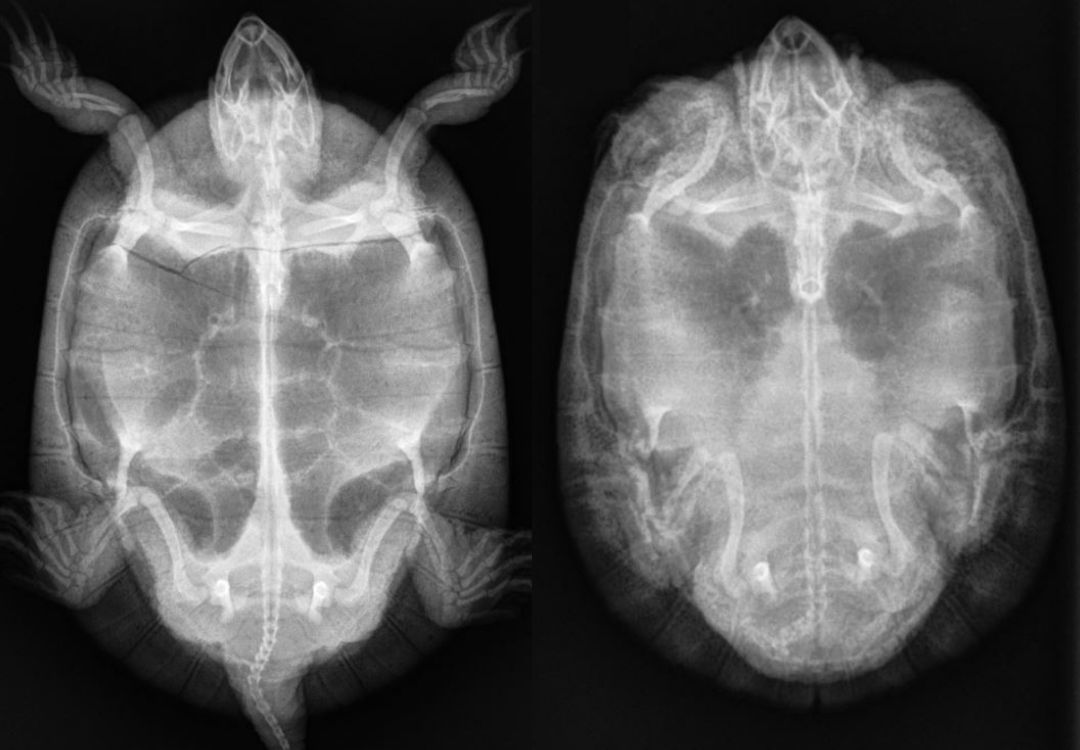

Three western painted turtles were kept for many years, the oldest taken from its habitat in 2016. All three turtles are being treated for metabolic bone disease (MBD), ocular swelling, edema (tissue swelling), and abnormal shell development. These health issues were caused by insufficient diet and care.

The mother of three eastern gray squirrels died when they were several weeks old. After three months of attempted care by a member of the public, the young squirrels were brought to the DCHS Wildlife Center. At admission, they had thin fur coats and a thin body condition likely caused by nutritional imbalance. They have been treated for those problems, but are also being monitored for displaying inappropriate behaviors due to being too accustomed to humans. This phenomenon is known as tameness.

It is difficult to reverse bad behavior shown by any young animal once it’s been learned. An animal becomes accustomed to its environment, habituating to its surroundings and following a daily routine. These young squirrels were raised to know the kindness of humans and now identify them as safe and as a good source of food, says Jackie Sandberg, Wildlife Training Supervisor. She adds that the only tactics wildlife rehabilitators can use to correct this behavior include severely limiting human interaction, making unfamiliar and loud sounds when entering an enclosure, and making people appear scary.

Tameness and imprinting can permanently hinder or endanger the life of a wild animal, and it can be dangerous for the public as well.

“In cases of imprinting, a wild animal may no longer be able to identify with its own species or reproduce successfully, and if tame, may approach people regularly,” Sarah Karls, Licensed Wildlife Rehabilitator at the Wildlife Center, says .

Paige adds, “When a wild animal does not fear people, it can be dangerous for the general public since those animals are more likely to be aggressive and bite. A healthy fear of people in wildlife prevents human and animal conflicts.”

“The goal of wildlife rehabilitation is to release animals that display appropriate behaviors towards people and other animals,” says Jackie.

While there is still hope that the squirrels can be rehabilitated and released after winter, it will take significant time, effort, and assessment by many here at DCHS. Unfortunately, Wildlife Center staff say the turtles may not be releasable at all due to their poor health. Regular behavioral and medical evaluations will help DCHS rehabilitators to document progress or regression over time.

Typically, it takes much longer to rehabilitate animals that have been kept for weeks or months in a home setting. They may need extensive socialization with their own species or supplemental treatments to reverse nutritional deficiencies. They also need to be taught necessary skills to survive in the wild, since they did not learn them while being raised as a pet.

“This can vary, but oftentimes when we are dealing with severe habituation or nutritional deficiencies it can take upwards of 3-6 months to attempt to resolve these issues,” Paige says. But, she adds, in some cases the animal may no longer be suitable to a life in the wild.

Animals that need to stay longer can take more time to care for due to their often-complex medical issues, and take up cage space, food, and medical supplies that may be needed for other wildlife. In the case of the turtles, what could have been a quick phone call giving advice to the finder has become months of rehabilitation and likely a life in captivity for these turtles.

Sarah says, “If an animal were to be brought in right away -- or even better, if the finder of an animal were to call us before taking an animal from the wild -- we could potentially help that finder reunite the animal with its wild parents, admit the animal, and avoid behavioral/nutritional issues for a much faster release. We could also inform them if that animal truly needs help.”

If you’ve found an injured or sick wild animal, click here for what steps to take. If you’ve found an orphaned wild animal, click here for more information on what you should and should not do.