Anticoagulant rodenticides have been used by humans since their development in the 1950’s, the first of which was a multi-dose product called Warfarin. Multi-dose (or first-generation) rodenticides typically work when small amounts of poison, mixed into a bait, is ingested over the course of a few days; single-dose (or second generation) rodenticides are more potent and can cause mortality after the first time the bait is eaten. Today, some of these toxic chemicals are sold commercially as common household “pest control” products, and others are distributed by licensed applicators.

If you did not already know, anticoagulant rodenticides are used to kill target “nuisance” animals such as mice and rats or other rodents that invade people’s homes. First and second-generation rodenticides work to interrupt necessary bodily functions in different ways, but generically, they inhibit an enzyme used by the liver to process Vitamin K or by altering the process of how the liver operates. In effect, clotting factors are kept from being available at appropriate levels in the blood, and when those factors are not available, then blood-clotting cannot occur.

The target experiences severe internal or external hemorrhaging, usually until death, depending on the dose and type of anticoagulant that was ingested. According to the National Pesticide Information Center, targeted animals that ingest anticoagulant rodenticides are noted to experience symptoms such as difficulty breathing, weakness, and lethargy in addition to: “coughing, vomiting, blackened stool, tarry blood, paleness, bleeding from the gums, seizures, bruising, shaking, abdominal distention and pain.”

The ethics of rodenticide use is often overlooked from the perspective of animal welfare because of the benefits they offer in ridding humans of “pests” that exist within our shared living spaces. Even the American Association of Veterinary Medicine (AVMA) states that rodenticides are efficient and cost effective in their 2019 Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals. However, this guidance also shares a myriad of concerns to consider in their use:

“For baited agents intended for free-roaming animals, accidental exposure of non-target species to the bait or poisoned carcasses and the environmental fate of unconsumed bait are of concern. Also in consideration with lethal oral agents are the severity and duration of clinical signs before death (i.e., degree of pain and suffering), the potential health and psychological hazards to human personnel who may witness distress in dying animals, and the negative public perception of animals being deliberately poisoned. For some species, the efficacy of rodenticides can vary substantially, and concern regarding non-target toxicosis is high.”

While the focus of rodenticide use is narrow (i.e., they can permanently get rid of many nuisance animals in one area), there are more than just rodents or animal pests that can be harmed because of their application. Primary poisoning occurs when a target animal eats rodenticide bait directly, but secondary poisoning occurs when another animal eats the primary-poisoned prey. Not only can this include wildlife predators, such as raptors, foxes, or snakes, but it could also be a danger for companion animals that free-roam outdoors, like dogs and cats.

What can rodenticide toxicity look like for non-target animals that predate on baited rodents? An agonizing, slow, and painful decline in health that may not be reversible and can sometimes lead to their death. Treatment for rodenticide poisoning needs to be a rapid response to be effective, but it depends on what chemical was used and when an animal was exposed. Second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides can be stored in the liver and are harder to get rid of, and there are other non-anticoagulant rodenticides on the market that kill rodents by other means. The only known treatment for anticoagulant rodenticides includes supportive care and supplements, like giving Vitamin K directly, to help stimulate the production of clotting factors to help reverse effects of the poison.

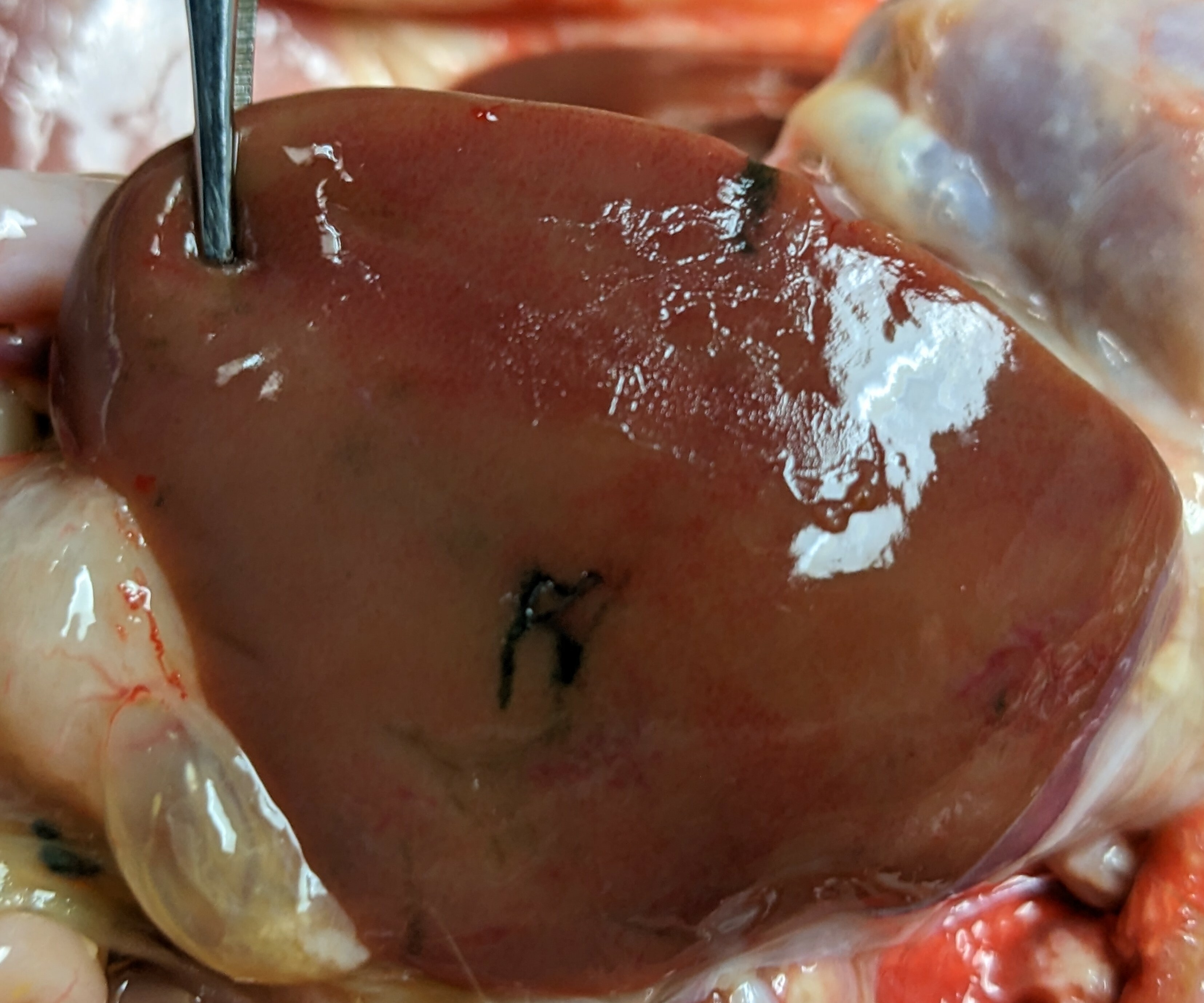

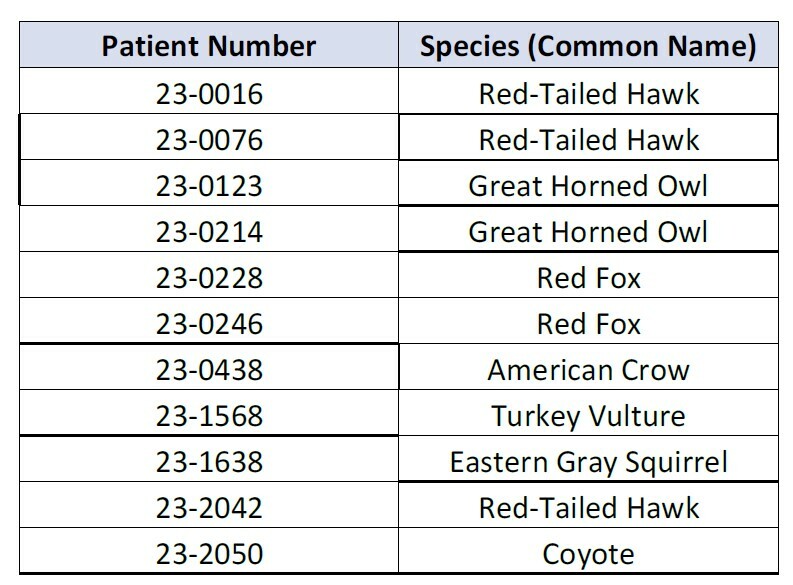

Red-tailed Hawks #23-0016 and 0076, both admitted at the beginning of last year, are examples of what wildlife rehabilitators must deal with when it comes to unintended consequences of using rodenticides. Initially, each bird received an exam by our team of licensed rehabilitators during which the birds were found to have symptoms of rodenticide toxicity. Often, this includes excessive bruising, depression, or anemia. Anemia is identified through standard intake diagnostics such as baseline bloodwork, where an animal’s measure of red blood cell mass. or packed cell volume (PCV), is evaluated. Hawk #23-0016 had a PCV value of 9%, where normal values would be above 35%, and the bird sadly passed away two days later despite receiving emergency care.

The blood tests that we have available to us at DCHS’s Wildlife Center are not able to specifically look for issues with clotting or for toxins like rodenticide. At DCHS’s Wildlife Center, we are able to test something called the packed cell volume, or PCV, which can give us an idea of how many red blood cells are in the body. While a low PCV can be caused by anticoagulant rodenticide toxicity, there are many other causes of a low PCV. Other tests exist but are not useful for various reasons. Laboratory tests that look for prolonged clotting are only available for mammals, are moderately expensive, and can take a few days to get results. Testing blood and tissues for the presence of rodenticide is expensive and can take around a week to get results, which is too long to be useful in treating patients in rehabilitation. Our staff must use their best judgement based on the animal’s mentation, the degree of bruising and bleeding, and their PCV value to determine if rodenticide toxicity is the likely diagnosis.

Hawk #23-0076 was noted to have “large hematomas from all phlebotomy sites,” meaning that large bruises appeared at each of the locations where blood was drawn from. Temporary pressure bandages were added to keep the bird’s blood from continuing to flow out from venipuncture sites once excessive bleeding was identified. Our veterinary team suspected coagulopathy, which is a condition where the blood has the inability to form clots. This is a problem that is always alarming and often stems from ingestion or exposure to anticoagulant rodenticides.

Left untreated, anticoagulant rodenticide toxicity could put animals at risk for continued anemia, organ failure, and potentially death, such was the case for Red-tailed Hawk #23-0016. Luckily, Red-tailed Hawk #23-0076 hawk was one of few patients admitted in 2023 that were evaluated quickly by our licensed staff team and could be provided with expert medical attention. This bird was provided with supportive care for a month and a half before it was stable enough to be released back into the wild where it was found.

Jackie Sandberg is the Wildlife Program Manager at DCHS's Wildlife Center